This is an edited and updated compilation of a very long thread I posted on Twitter/X in instalments in 2023 and 2024.

At the time of writing in June 2025, the BBC is still broadcasting on longwave, so this story remains to be concluded!

The BBC before longwave

Longwave broadcasting – meaning the transmission of public radio broadcasts using wavelengths longer than 1,000 metres (frequencies below 300 kHz) – did not begin in Britain.

From 1919, Dutch station PCGG regularly broadcast what became known to British listeners as the "Hague Concerts", using wavelengths up to 1,050 metres. In Paris, Radio Eiffel Tower opened in February 1922 on a wavelength of 2,600 metres – around 115 kilohertz (kHz).

In contrast, all the earliest BBC broadcasts were on mediumwave. At its formation in November 1922, the BBC inherited three MW transmitters from its founding companies: 2LO London, 2ZY Manchester and 5IT Birmingham. By the end of 1924 it had built six more "main" MW stations and 11 relay stations.

All 20 of those early BBC transmitters were on frequencies between 600 and 1000 kHz (wavelengths between 500 and 300 metres). This compares to the modern mediumwave band in Europe which has channels between 531 and 1602 kHz (wavelengths between 565 and 187 metres).

The BBC's early transmitters were licensed to have a maximum power of, by modern standards, a rather modest 1.5 kilowatts (1.5 kW). In reality, they were even less powerful than that, and the relay stations were just 100 watts (0.1 kW). This gave the BBC a group of stations that only covered individual cities and their immediate surroundings, rather than a national service.

Individual stations could link up to relay the same programme but this was hampered by the poor quality of long-distance phone lines. This became a regular source of friction between the BBC and the Post Office, which held the monopoly on the telephone service. The BBC saw the potential of providing national coverage from a single longwave transmitter.

The BBC starts longwave broadcasting in 1924

In July 1924, the BBC began longwave broadcasts on 187.5 kHz (a wavelength of 1,600 metres).

They came from a 15-kW transmitter at the Marconi factory in Chelmsford (Essex). The callsign 5XX was used.

Permission for the BBC to use longwave was given by the Postmaster General, as head of the General Post Office, in June 1924. (Since 1868, the GPO had been the regulator for, first, all telegraphs in the UK, and then radio transmissions.)

Test transmissions began on 9 July, with an official opening ceremony on 21 July.

Reports of reception came in from all over the country.

Initially, the 5XX longwave transmitter simply relayed the programmes of 2LO London, and only in the evening. From December 1924, some alternative programmes were offered.

1925-1930: 5XX moves from Chelmsford to Daventry

A year after the start of longwave broadcasts, the 15-kW Chelmsford transmitter was replaced on 27 July 1925 by a new 25-kW transmitter at Daventry (Northamptonshire). It continued to use the frequency of 187.5 kHz and the callsign 5XX. It also used the ID "High Power Programme".

The increased power and Daventry's more central location meant many listeners now had a choice between 5XX and their local BBC station.

Around 80-85% of UK population was said to be in range of Daventry's signals, much higher than the figure for all of the BBC's twenty mediumwave stations put together.

The 5XX transmitter at Daventry was eventually scrapped in 1949, but three valves from it are now in Daventry's town museum.

|

| The Daventry transmitter, installed in 1925 |

On 3 July 1927, 5XX's frequency was adjusted slightly from 187.5 kHz to 187 kHz.

Also in 1927, an international agreement, the Washington Convention, restricted the extent of the longwave band for broadcasting purposes to frequencies between 160 and 224 kHz (wavelengths of 1,875 to 1,340 metres). The BBC was already within this band but some European stations were outside it and had to move.

(The extent of the band was later extended again, and since 1978 it has allowed for broadcast stations to operate between 153 and 279 kHz – that is, wavelengths of 1,960 to 1,075 metres – on channels that are multiples of 9 kHz: 153, 162, 171, 180, 189, 198, 207, 216, 225, 234, 243, 252, 261, 270, 279.)

On 11 November 1928, 5XX's frequency moved from 187 to 192 kHz (1562 metres) in line with an international agreement known as the Brussels Plan. The move reduced interference from Germany's Deutschlandsender transmitter at Zeesen, near Berlin, which had moved from 240 to 183.5 kHz in October 1928.

The Brussels Plan was effective for only a few months, and in its third frequency change in less than two years (albeit a very small one), on 30 June 1929, 5XX moved from 192 kHz to 193 kHz in line with the Prague Plan.

1930-1934: From 5XX to the National Programme

On 9 March 1930, the BBC stopped using callsigns for transmitters in its on-air announcements, replacing them with "National" and "Regional" IDs. The longwave service was now called the National Programme. (Internally, however, the BBC continued to refer to the Daventry longwave transmitter as 5XX.)

Most listeners now had a choice between the National Programme and at least one Regional Service.

Alongside the Daventry longwave transmitter on 193 kHz, the BBC's new National Programme was also relayed by a mediumwave transmitter at Brookmans Park, just north of London.

Additional mediumwave relays for the National Programme

were opened over the next three years at Moorside Edge (near Huddersfield),

Westerglen (near Falkirk) and Washford (on the Somerset coast).

(The Washford transmitter was transferred to the West Regional Service in 1937.)

By 1932, the Daventry longwave transmitter carrying the National Programme on 193 kHz was advertised as running at 30 kW.

From late 1933, the BBC faced competition on longwave from Radio Luxembourg, whose English service on a 200-kW longwave transmitter could be heard in much of the UK. It was particularly popular on Sundays, when the BBC avoided light entertainment and didn’t start broadcasting until the afternoon.

By 1934 there were also longwave stations in 13 other countries: Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Romania, Sweden, Turkey and the Soviet Union (USSR).

On 15 January 1934, Daventry's LW channel moved from 193 to 200 kHz (1,500 metres) in line with yet another international frequency agreement, the Lucerne Plan. It was the fifth LW frequency the BBC had used in a decade but would remain unchanged until 1988.

"Fifteen hundred metres" became a familiar phrase to generations of BBC listeners.

1934-1939: Move to Droitwich, planning for war

On 6 September 1934, the BBC opened a new 150-kW longwave transmitter at its new station at Droitwich, south of Birmingham. That was the maximum power allowed under the Lucerne Plan. (Though the plan allowed the USSR to continue to run a 500-kW transmitter at Moscow.)

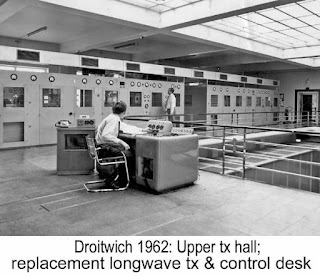

Here's the new Droitwich longwave transmitter, pictured in 1937 (transmitter in the background, control desk in the foreground).

|

| The Droitwich transmitter, installed in 1934 |

After a month of sharing the duty of airing of the National Programme with Droitwich at different times of the day, the 5XX transmitter at Daventry closed on 7 October 1934.

Daventry continued to transmit on shortwave. After the Second World War it also used mediumwave. It's the only BBC station to have transmitted on all three wavebands.

Along with its much higher power, the new transmitter at Droitwich offered greatly improved audio quality, radiating audio frequencies between 30 and 8,000 Hz. That's better than the current BBC LW service, which limits the upper range at just over 5,000 Hz.

Over the coming decades, "Droitwich" became a familiar marking on dials of radio sets in Europe – at 1500 metres (200 kHz), roughly in the middle of the longwave band.

The BBC had the exclusive use of 200 kHz until well after the Second World War.

The Droitwich longwave transmitter broadcast the BBC National Programme from 10.15am (with a later start on Sundays) until midnight.

On 30 June 1938, having resigned earlier in the day as BBC Director-General, Sir John Reith drove to Droitwich in the evening and shut down the longwave transmitter at the end of the day's broadcasts, signing the visitors' book at 1.10am on 1 July: "John Charles Walsham Reith – late BBC"

Also in 1938, the BBC began planning for war. The Air Ministry said that, in the event of hostilities, all mediumwave transmitters would have to be in synchronised networks on shared frequencies, to confuse enemy direction-finding.

As there was only one longwave transmitter it would have to close to prevent its use as a beacon.

War brings end of longwave broadcasts

After the German invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939, the BBC implemented its emergency plans, including the end to all longwave broadcasts, to prevent enemy use of Droitwich as a navigational aid.

The BBC National Programme and all BBC Regional services closed at 7pm on 1 September.

The Droitwich LW transmitter on 200 kHz stayed on the air briefly, but only to tell listeners to retune to the new BBC Home Service which opened at 8.15 that evening on two mediumwave frequencies (668 and 767 kHz).

The BBC did not resume longwave broadcasts until 1941.

The idle longwave transmitter at Droitwich was converted to work on mediumwave and its power increased from 150 to 200 kW. From 7 October 1939, it joined a network of transmitters elsewhere in the country that had been using 1149 kHz to carry the BBC European Service since the start of the war.

The BBC was able to continue using mediumwave because of "grouping" and "synchronisation".

For its UK listeners, the BBC used two groups of transmitters (each roughly covering the north and south of the country).

Initially, each had four transmitters on the same frequency. This "grouping" befuddled anyone trying to take a bearing on an individual transmitter. The "north" group was on 767 kHz. The "south" group was on 668 kHz.

Both carried the same programming – the new BBC Home Service. There were no local or regional opt-outs.

The system worked because the frequencies of the individual transmitters in each group were carefully measured daily and adjusted so they were as identical as possible ("synchronised"). This "grouping" and "synchronisation" was a British speciality.

Germany never fully adopted synchronisation, which caused it no end of problems as the allied bombing campaign developed. The Germans were regularly forced to temporarily silence their radio stations when "enemy terror raiders" approached the Reich.

A similar system was also used by mediumwave transmitters carrying the BBC European Service, along with aerials that impaired the ability to use signals as directional beacons. This allowed the European Service to transmit on 1149 kHz from September 1939, adding 804 kHz in February 1940 and 1050 kHz in October 1940.

Longwave resumes in 1941 – the interim solution

As German air raids on the UK eased after May 1941, the Air Ministry agreed that the BBC could resume longwave broadcasts, with suitable precautions.

The BBC was keen to broadcast to Europe on longwave and had two plans on how to do this – an interim solution and a permanent one.

The interim solution was to re-convert the Droitwich longwave transmitter back to working on that waveband. As described above, it had been converted to work on mediumwave when longwave broadcasts stopped at the start of the war.

On 16 November 1941, the BBC resumed longwave broadcasts after a break of more than two years. The re-converted Droitwich transmitter, with its power increased to 200 kW, began broadcasting the BBC European Service on the transmitter's pre-war frequency of 200 kHz.

By chance, next to the BBC on the longwave dial was

Deutschlandsender on 191 kHz.

Unlike the BBC, Germany had kept its longwave transmitter going after war started, though it had to be switched off when enemy aircraft approached. This gave the BBC several opportunities.

When Deutschlandsender had to close it was just a small turn of the dial for listeners to retune to the BBC. And it must have been hoped that the German jamming of the BBC on 200 kHz would also affect reception of Deutschlandsender on the adjacent channel.

By 1941, BBC news bulletins in German were being aired regularly between 6am and 11pm German time. Soon after, a 15-minute bulletin was added at 2am.

To confuse Luftwaffe direction-finding of the Droitwich transmitter, two "spoiler" or "masking" transmitters were also used on 200 kHz: the old Daventry 5XX 30-kW transmitter (which had closed in 1934) and a newly installed 15-kW transmitter at Brookmans Park, near London.

New longwave transmitter at Ottringham

Droitwich was the interim solution. The permanent one was the BBC's plan to build a new and extremely high-power longwave station on the east coast, taking advantage of the sea path to the continent to blanket the whole of Germany with a listenable signal, day and night.

The "ground wave" signals of longwave and mediumwave transmitters lose much less of their power over long distances when travelling over water than they do over land.

The new station would use an innovative transmitter – in fact, four transmitters in one. Each of these was 200 kW in power (in itself, very powerful). The station could run each one separately, so airing four different programmes simultaneously on four different frequencies.

Or the transmitters could be combined (two, three or all four together) to give up to 800 kW for a single programme on a single frequency.

This would be the most powerful broadcasting station in the world.

A site for the new station was found close to the coast at Ottringham, near Hull, and construction began. Each of the four transmitters was put in its own building, heavily protected against air attack. Even if one of them was hit by a bomb, the other three would keep the station on the air.

It had been hoped to get one transmitter on air in March 1942, but there were delays. It was a complex project. Separate buildings also had to be built for the control room, for equipment to combine the outputs of the four transmitters, and for the station's power generator.

There was a further delay when two of the 500-foot aerial masts collapsed in August 1942 while they were being erected. In the end, the Ottringham station wasn't completed until January 1943. Regular transmissions began on 12 February 1943.

It was decided to use three of the transmitters in combination (that is, with a total power of 600 kW) on 200 kHz longwave for the BBC European Service.

The fourth transmitter was run at 30 kW and joined the northern group of the BBC Home Service on 767 kHz mediumwave.

Ottringham continued to broadcast the BBC European

Service in German and other languages on 200 kHz longwave until the end of the

war.

An off-air recording of Ottringham in 1945

In one of the wonders of broadcasting history, there is an off-air recording of the Ottringham station, as received in Nazi-occupied Europe.

The recording was made by Danish radio and recording

enthusiast Aage Schnedevig, who worked in secret to make recordings of the BBC

to help the production of clandestine newspapers.

His simple disc recording apparatus is now in Denmark's national museum. –

On 4 May 1945, Schnedevig recorded the BBC Danish service at 8.30pm Danish time (which was also 8.30 Double British Summer Time – 1830 GMT). Here's a full recording of the 30-minute broadcast. You can hear the (ineffective) German jamming start shortly after the beginning.

At the start of the broadcast, you can hear announcer Johannes Sørensens say that it can be heard on three shortwave bands and "femten hundrede meter" (fifteen hundred metres) – the wavelength of the BBC's longwave transmitter (equivalent to a frequency of 200 kHz).

Less than five minutes into the broadcast, you can hear Sørensens pause and switch off his microphone as a colleague comes into the studio to tell him that all German forces in Denmark are surrendering.

Sørensens switched the microphone back on to say:

I dette øjeblik meddeles det, at Montgomery har oplyst, at de tyske tropper i Holland, Nordveststyskland og i Danmark har overgivet sig. (At this moment it is announced that Montgomery has announced that the German troops in Holland, Northwest Germany and Denmark have surrendered.)

The names you can hear being read out from 26:00 in the recording are coded messages to the Danish Resistance.

This broadcast became known to Danes as the Frihedsbudskabet ("Freedom Message") and Schnedevig's recording is now aired each year by Danmarks Radio at the exact moment of the original transmission.

The BBC's foreign services were grouped in colour-coded networks. This was purely an internal arrangement – the colours were never announced on air. The number of such networks, and which languages were in each one, varied over the years.

In the latter part of the war, Ottringham was carrying the Blue and Grey Networks, targeting west, central and northern Europe. German was among the languages in the Blue Network while the Grey Network was for Nordic countries. Both also included broadcasts in English.

Other wartime work

Along with broadcasts, BBC longwave transmitters helped the war effort in other ways. The old Daventry 5XX unit served as a "masking" transmitter for its younger sisters at Droitwich and Ottringham until December 1944. It was then handed over to the RAF to carry Morse on 530 kHz.

Daventry also housed a low-power longwave transmitter used by the Air Ministry for civil aviation as both a beacon on 151 kHz, and for communications with aircraft between 280 and 380 kHz.

The Droitwich longwave transmitter was used from May 1942 onwards in Operation WASHTUB. This involved it coming on the air unannounced (and without accompanying "masking" transmitters) during the night to act as a beacon for RAF bombers returning home from raids.

Post-war reorganisation

The BBC began planning its post-war activities in 1941. By early 1945, the plan for the UK audience was:

- Regionalise the Home Service, with all listeners able to hear at least one, possibly two, regions

- Provide two other national radio stations, each with its own distinct character and genre of programmes

- Resume the TV service

As wartime domestic broadcasting had consisted of just two national radio stations, with no regionalisation at all, the plans needed additional transmitters and frequencies, which would have to come at the expense of the BBC European Service – and reviving longwave for UK listeners after a six-year break.

In line with the plans, on 29 July 1945 the BBC launched its new "Light Programme" on 200 kHz (1500 metres) from the Droitwich longwave transmitter, for UK-wide coverage.

Between 1941 and 1945, 200 kHz had carried the BBC's European Service, from various transmitters.

See this excellent look by Andy Walmsley at what you could hear "on the Light" during its 22-year history (1945-1967).

And here's a montage of clips that Andy put together from the Light, including its Oranges & Lemons theme, and the tune and announcement that for years started millions of UK Sunday lunchtimes: "The time in Britain is 12 noon, in Germany it's 1 pm..."

That was the opening announcement to Two-Way Family Favourites, with its equally memorable signature tune With a Song in My Heart, recorded by André Kostelanetz. In its way, a signature tune for 1950s Light-Programme Britain as a whole.

The power of the Droitwich transmitter had been increased from 150 to 200 kW for its wartime work, and it continued to use this higher power after 1945 for the Light Programme.

For listeners some distance from Droitwich, the Light Programme was also aired on mediumwave by three transmitters of 60 kW and six of lower power. All were on 1149 kHz (261 metres).

Like 200 kHz longwave, 1149 kHz had been used during the war for the BBC European Service.

Among those who would have listened to the Light Programme's mediumwave relays were listeners who had bought a wartime Utility Radio, which did not have a longwave band.

However, it seems that listeners without a longwave set were not a consideration when planning these MW relays, as none were provided in the Midlands, Wales, East Anglia or most of southern England, where Light Programme reception on longwave was good.

Along with the BBC, Radio Luxembourg also revived the use of longwave after the war for the British audience. Luxembourg's English service had begun in 1933.

However, this was not as profitable for Luxembourg as it had been in the 1930s. BBC programmes had improved and were tougher competition than they had been.

In 1951, Radio Luxembourg switched its longwave transmitter to its more lucrative French service and moved its English service to 208 metres mediumwave (1439 kHz).

Post-war longwave broadcasting from Ottringham

The Light Programme's launch in July 1945 on 200 kHz left the BBC looking for another longwave frequency for its European Service, which had used 200 kHz since 1941.

From 1943, these had come from the purpose-built high-power station at Ottringham (see above).

The BBC was particularly keen to keep the European Service on longwave as in 1945 the number of mediumwave channels available to the service was cut from three (804, 1050, 1149 kHz) to two (977, 1122), and then in 1946 to just one (1122).

The Ottringham longwave transmitter used various frequencies for BBC European Service from 1945. Eventually, it settled on 167 kHz (1796 metres), though with reduced power - 200 kW compared to the 600 kW used in the war.

For completeness, it should be added that although the BBC cut back its European Service to just one mediumwave frequency from UK-based transmitters after 1946, it also hired time on mediumwave transmitters in Germany (at Norden, on 658 kHz) and Austria (at Graz, on 886 kHz).

At this time (1945-46), the BBC's German output was seen as particularly important. For a while, it was in effect a "home service" for the British-occupied sector of Germany while Nordwestdeutscher Rundfunk (NWDR) was being established, under British supervision.

Because of this, the output of the BBC German service, almost five hours a day in 1944-45, was increased substantially at the end of the war, and then again at the start of 1946.

Changes caused by the Copenhagen Plan

In 1948, an international conference in Copenhagen drew up a new European frequency plan for longwave and mediumwave. Such conferences had been held regularly in the 1920s and 1930s, but there had not been a planned reorganisation of the bands since the so-called Lucerne Plan in 1934.

The Copenhagen Plan had modest good news and a major disappointment for the BBC's longwave operations. The good news was that the BBC continued to have exclusive use of 200 kHz, and the power limit on that frequency was raised to 400 kW.

The pre-war Lucerne Plan had put a 150-kW limit on the power of the Droitwich longwave transmitter. The BBC had raised the power of the transmitter to 200 kW during the war and continued to use that power when the Light Programme was launched.

To take advantage of the new 400-kW power allocation, the BBC turned to a readily available replacement for the 1934 transmitter. This was Droitwich's so-called HPMW (High-Power Medium Wave) transmitter which had come into service in 1941.

HPMW was converted to run on longwave (and renamed HPLW).

It began carrying the Light Programme with 400 kW on 15 March 1950 when the

Copenhagen Plan was implemented.

Also from that date, all the Light Programme's mediumwave transmitters moved from 1149 kHz to 1214 kHz.

The Light Programme was also carried on 1214 kHz in north-west Germany for British forces - though in many cases listeners there would have been able to get good reception direct from Droitwich on longwave.

Ottringham closes

If the Copenhagen Plan brought some good news for Droitwich, it was a major disappointment for Ottringham. The UK was allocated just a single longwave channel.

Ottringham therefore had to stop using 167 kHz longwave in 1950. Instead, it carried some early morning BBC European service programmes on 200 kHz before the Light Programme began its day. It also used 1295 kHz mediumwave at various times of day.

But there was further bad news for Ottringham. Budget cuts

forced the closure of the station altogether, and it shut in February 1953.

Fortunately, all four of Ottringham's 200-kW transmitter units were saved.

After Ottringham closed, Droitwich took on responsibility for airing the early morning BBC European service programmes on 200 kHz before the Light Programme began its day.

Ottringham's closure was a real pity, and a historical "What if?" of British broadcasting. Able to project high-power signals on both long and mediumwave deep into Europe (including the USSR), Ottringham would have been a very useful tool for the BBC during the Cold War.

One Cold War possibility for an Ottringham-that-never-was could have been more broadcasts on Russia's own longwave frequencies, in the way done by the Voice of America from its transmitter near Munich on 173 kHz.

VHF/FM

In 1955, the BBC began rolling out a network of transmitters on FM – or VHF (very high frequency) – to use the term of the time – across the country.

By August 1958, the network was said to cover 95% of the UK population with FM signals of the Light Programme, Home Service and Third Programme.

Though 95% of the population may have had FM signals, the proportion using them was very much less than that. Take-up of FM was slow. For many years, long and mediumwave remained the mainstay of reception – including the Light Programme on longwave.

Even by 1972, the BBC said that not quite half of households had an FM receiver.

For many, there was little incentive to buy an FM set. There were very few extra programmes to be heard, though it did allow listeners in East Anglia to hear some local output – until then the BBC had treated the region as part of the Midlands.

FM also avoided interference from foreign stations after dark. But that was a problem on mediumwave, not for Light Programme listeners on longwave. The audience on LW remained huge, especially as "the Light" carried the BBC's most popular programmes.

Change of longwave transmitters at Droitwich

By the early 1960s it was time to renew the longwave transmitter at Droitwich. The HPLW (High Power Long Wave) transmitter was retired. It had been used since 1941, first on mediumwave for the European Service then the Third Programme, and since 1950 on longwave for the Light.

HPLW was replaced by two of the four 200-kW units recovered from the old Ottringham station when it closed in 1953.

The other two units from Ottringham were used (from 1961) as replacements for Droitwich's MW relay of the Home Service.

The two Ottringham longwave transmitters, coupled together to give 400 kW of output power, started to carry the Light Programme on 200 kHz from Droitwich on 18 September 1962.

BBC shares longwave channel with the USSR

Initially, Mayak's transmissions on 200 kHz were relatively modest, both in the number and transmitters used and the times of day they were on the air. That changed in the 1970s, as described below.

Launch of Radio 2 on longwave

On 30 September 1967, the BBC launched a new service, Radio 1, which inherited some of the Light Programme's music shows. Most other Light Programme output formed the core of the new Radio 2.

Radio 2 continued to use 200 kHz longwave and the Light Programme's UK-wide FM network.

The Light Programme's mediumwave network (1214 kHz) was allocated to Radio 1, with high-power transmitters added at Droitwich and Washford, and low-power ones at several other places.

This left Radio 2 without any mediumwave signals at all, leaving some listeners in Scotland who didn't use FM with unsatisfactory reception from longwave.

To deal with this, low-power mediumwave relay stations for Radio 2 were opened in late 1967 and 1968 in Scotland's four largest cities: Glasgow, Edinburgh, Aberdeen and Dundee. All were on 1484 kHz.

Outside Scotland, there seem to have been few complaints, if any, from listeners that they could not hear Radio 2 on mediumwave. But this had been a lesson for the future about longwave coverage in Scotland.

Overnight broadcasts to Europe on longwave

As it had done since 1953, Droitwich longwave continued to air the BBC European service in the early morning. Details varied over the years. For example, the overnight schedule in 1968 was:

0200 Radio 2 closedown

0400-0430 BBC World Service in English

0430-0515 BBC German service

0515-0530 BBC Czech service

0530 Radio 2 opens

This usage was reduced after September 1972 when the BBC European Service got the use of an extra mediumwave frequency (1088 kHz). After that, there was only a limited use of longwave in the early hours for European broadcasts (in Russian and English).

Using longwave for BBC Russian was a nightly raid on Soviet airspace. As noted above, by the USSR was using 200 kHz for its Mayak station. The most imaginative BBC transmission was the 0245-0300 GMT (0545-0600 Moscow time) news in Russian, just before Mayak started using 200 kHz at 0300.

The 1978 changes - what problems were they designed to solve?

By 1975, 200 kHz longwave had been carrying the Light Programme and then Radio 2 for 30 years. This continued to be a very satisfactory frequency. However, the same was not the case for much of the rest of BBC radio. Some of the problems:

Firstly, Radio 4 was not a truly UK-wide service. Outside southeast England it was relayed on mediumwave and FM frequencies shared with regional output, hogging a large number of MW channels.

Radio 4's mediumwave regionalisation in England ended in the early 1970s, allowing R4 to give up frequencies to BBC local radio (1457 kHz), the European service (1088 kHz) and the new commercial stations (1151 kHz). But by 1975, Radio 4 was still using high power on six other MW frequencies.

The high-power Radio 4 frequencies by 1975 were 692, 908 and 1052 (England), 809 (Scotland), 881 (Wales) and 1340 (N Ireland). Radio 4 was also on low power on six other mediumwave frequencies (five in southwest England and one in Northern Ireland).

Listeners in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland still had to put up with their old Home Service MW and FM frequencies being shared between regional programming and that of Radio 4. What they wanted was a choice at all times between the two separate services.

Next, Radio 4's extensive use of mediumwave meant that Radio 1, the BBC's most popular service, had to make do with its least satisfactory AM network (1214 kHz).

To compound the problem, Radio 1 was only on FM (borrowing Radio 2's FM network) at very limited times of the day.

BBC radio in 1970s had an array of split uses of AM & FM:- Radios 1 & 2 shared an FM network

- Radio 2 was sometimes relayed on BBC local radio (AM & FM)

- Cricket on Radio 3 AM

- Regional use of Radio 4's FM transmitters

- Educational & children's progs on Radio 4 FM

Finally, although the BBC European service had a good MW frequency (1295) for after-dark coverage, those used during daytime (809 and 1088) were unsatisfactory. It needed a frequency at the low end of the MW band to take advantage of better groundwave coverage by longer wavelengths.

- To tackle the problems outlined above

- To implement a new international agreement on the use of longwave and mediumwave – the Geneva Frequency Plan of 1975.

At the time, the UK press criticised the Geneva Plan and

the BBC, complaining that:

- Listeners would have to learn to find their favourite stations on new wavelengths

- One of the UK's mediumwave allocations (1215 kHz) would suffer major interference after dark from Albania

In the end, the new plan and the BBC reorganisation

provided a substantial improvement for most listeners.

The new plan took effect on 23 November 1978.

The key to the changes was Radio 4 giving up all six of its high-power mediumwave networks. This gave several benefits:

Releasing three of the frequencies meant that Radio Wales, Radio Scotland and Radio Ulster each got the exclusive use of a high-power mediumwave channel, rather than having to be an opt-out from Radio 4.

The other three high-power Radio 4 MW channels were, along with a frequency released by the BBC European Service, used to make two good UK-wide mediumwave networks for Radio 1 (1053 and 1089) and Radio 2 (693 and 909).

This gave Radio 1 very much better coverage than its previous single-frequency network (1214 kHz), which had many "mush" areas where the signals from two or more Radio 1 transmitters on the same frequency interfered with each other.

"Radio 4 UK" on longwave

In return for giving up all its high-power MW transmitters, Radio 4 took over Radio 2's longwave allocation, which meant it could finally become a truly single UK-wide service.

To emphasise Radio 4's new capability to cover the whole of the country throughout the day, from 1978 it started identifying itself as "Radio 4 UK", though this ID was dropped in 1984.

The new name was accompanied by a new piece of music, the Radio 4 UK Theme, composed by Fritz Spiegl. It was played at the start of each day's broadcasts from 1978. The dropping of the theme in 2006 provoked complaints.

Just over a year after Radio 4 went onto longwave, what may have been the single longest peacetime outage of the BBC's longwave broadcasts (that is, outside the wartime break between September 1939 and November 1941) came on 17 December 1979 when the Droitwich LW T-aerial – but not its two supporting 700-foot (213 metres) masts – blew down in a gale, silencing 200 kHz (though not from Burghead or Westerglen) for a few days.

A second BBC longwave frequency?

The 1975 Geneva Frequency Plan had a bonus for the BBC. Along with renewing its longwave allocation of 200 kHz (1500 metres) – used since 1934 – it gave the BBC an additional LW allocation of 227 kHz (1321 metres).

The BBC's initial plan was to use both 200 and 227 kHz to give UK-wide coverage for Radio 4. Alongside the existing 200 kHz service from Droitwich, a transmitter on the same frequency would be installed at Burghead (on the coast east of Inverness) to cover northern Scotland.

The two transmitters on 200 kHz would have a "mush area" in central Scotland where signals from both Droitwich (400 kW) and Burghead (50 kW) would be received at roughly equal strength, interfering with each other.

To cover the "mush area" area, the 227 allocation would be used by a third LW transmitter at Westerglen covering central Scotland. Many listeners in Scotland, Northern Ireland and the far north of England would be able to choose between 200 and 227 for best reception.

But this initial plan was abandoned when it was realised that Poland's 2,000-kW (two megawatts) transmitter on 227 kHz would interfere with the BBC to an unacceptable degree. It was therefore decided that Westerglen would also operate on 200 kHz.

The new plan therefore created two "mush areas" – one between Burghead and Westerglen, and the other between Westerglen and Droitwich. The BBC took several measures to mitigate this, including very slightly delaying the audio feed to Westerglen to avoid echoes.

The next measure was to provide a way of precisely locking not just the frequency but also the phase of the carrier waves of all three longwave transmitters. This is described in this paper.

Finally, some low-power mediumwave fillers were provided

for Radio 4:

- At Aberdeen on 1449 kHz (in the longwave mush area between Burghead and Westerglen)

- In Northern Ireland on 720, Carlisle on 1485 and Newcastle on 603 (in the mush area between Westerglen and Droitwich)

The new frequency plan was introduced on 23 November 1978. In advance, the BBC distributed stickers for people to put on their radio sets to show the new dial positions of Radios 1, 2, 3 and 4.

The reason why the BBC couldn't take up its 227 kHz allocation disappeared in 1991 when Poland's longwave mast on that frequency collapsed. Two replacement sites in Poland were eventually used, but neither of them put the same strength of signal into the UK.

By then, Radio 4 was well established on its single longwave frequency of 200 kHz and so the UK did not take advantage of the second LW allocation for broadcasting. Instead, the 227 allocation (which became 225 after 1988) was used for a while in the UK by baby monitors.

I suspect many parents with these baby monitors didn't realise that their neighbours could use an ordinary LW radio to eavesdrop on their homes.

Radio 4's FM and longwave opt-outs

From 1978 until 1991, longwave carried Radio 4's main service while R4's FM network was shared with other output.

At that time the BBC only had three UK-wide FM networks. Two were used by Radios 1/2 and 3. The third was shared by R4 with Radios Scotland, Cymru and Ulster.

In England, the Radio 4 service on FM had to share time with a large variety of other output, including Open University, schools and children's programmes, and parliamentary broadcasts. Many of these transferred to the new Radio 5 when it opened in 1990. In addition, in the early years of Radio 4 on longwave, its FM transmitters opted out of R4 to carry local programmes for East Anglia (until 1980) and South-West England (until 1982).

The "Radio 4 UK" branding, used by the longwave service from 1978 to emphasise that LW covered the whole country, was dropped in 1984.

In September 1991, with a dedicated Radio 4 FM network finally available throughout the UK, the main Radio 4 service was moved to FM. All opt-outs, such as the Daily Service, were moved to longwave.

What became Radio 4 longwave's best known opt-out – Test Match Special – joined the network in 1994. TMS had earlier been aired, from 1957, successively on the BBC Third Programme, Radio 3 and Radio 5.

Test Match Special's move to Radio 4 longwave came when Radio 5 Live replaced Radio 5. The final TMS on longwave was aired on 31 July 2023.

The longwave opt-outs were gradually reduced so that, by the time they ended altogether on 31 March 2024 the only regular ones were The Daily Service, Yesterday in Parliament and two extra daily shipping forecasts. After the date, 198 kHz carried exactly the same output as Radio 4's FM network.

In 1992, the BBC raised a proposal to drop Radio 4 from longwave and use the LW frequency for an all-news station. The plan was dropped after public opposition. Instead, the BBC launched Radio 5 Live in 1994 on the frequencies of Radio 5.

Use of the longwave service overnight

The 1978 changes also saw changes to LW's use by the BBC external services. In 1950-1978, the LW channel had carried some early morning BBC European services (mainly in foreign languages) before the Light Programme (after 1967, Radio 2) began its day.

After 1978, the BBC had much better use of mediumwave for reaching European listeners and so there was a slow transition to targeting the overnight relays on longwave to UK listeners rather than those on the continent.

But the move took time. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, BBC World Service in English was only relayed from 0300 UK time, suggesting that the main audience the BBC had in mind were early risers on the continent rather than those in the UK who wanted an all-night companion.

Later, the start time was brought forward to 0200 UK time, but it was not until 1986 or 1987 that the practice of relaying the World Service throughout the whole of Radio 4's silent overnight period was established. (Does anyone have the exact date?)

The 1978 changes also saw the end of the use of longwave for early morning BBC broadcasts in Russian, partly reflecting an expansion in the USSR's use of 200 kHz for its Mayak service.

Mayak's distinctive 10-note tuning signal, played just before every hour and half-hour around the clock, could often be heard in the UK after dark behind Radio 4's longwave signal.

Replacement of the transmitters in 1987 and 1988

In June 1987, the longwave transmitters which had been in

use at Droitwich since 1962 were replaced.

The two transmitters (each 200 kW in power, combined to give 400 kW) had originally been used at Ottringham for the BBC European service in 1943-53.

The new transmitters at Droitwich were two Marconi B6042 models, each of 250 kW, whose outputs were combined to give a total power of 500 kW. These transmitters continue in service to this day.

The other Radio 4 LW transmitters, at Burghead and Westerglen, were replaced in January 1988. At both sites, two modified Marconi B6034 50-kW transmitters (a model much used by the BBC on MW) were installed. They were each run at reduced power and their outputs combined to give 50 kW.

On 1 February 1988, the longwave frequency used by Droitwich, Burghead and Westerglen was changed from 200 kHz (a wavelength of 1500 metres) to 198 kHz (1515 metres), to meet the requirement for all LW and MW frequencies outside the Americas to be exact multiples of nine.

The BBC had used 200 kHz since 1934 and "fifteen hundred metres" had become a familiar phrase to generations of listeners.

RTS - radio teleswitching system

Another technical development took place in this period. After tests from 1979, in 1984 the BBC longwave signal began carrying data, using phase shift keying (PSK), to allow electricity companies to remotely control customers' appliances and meters.

The PSK data signal is inaudible to those listening to BBC programmes. More technical details of this service, also known as the radio teleswitching system (RTS), are in this leaflet from 1978-88.

The RTS service is now run by the Energy Networks Association.

BBC longwave provides national standard-frequency service

In 1945, when Droitwich resumed a longwave service for UK listeners (in the war all BBC LW transmissions had been for listeners in Europe) it also began providing a national standard-frequency service to a range of industrial, scientific and private users, guaranteeing the frequency of the signal on 200 kHz to be accurate to 2 parts in 10 to the power of 8 (10^8).

This meant that the carrier frequency of the Droitwich 200 kHz transmitter was guaranteed to be no lower than 199.999996 kHz and no higher than 200.000004 kHz, equivalent to an accuracy of one second over the course of 19 months.

Major improvements in accuracy were made in 1963 and again in 1967 when a crystal oscillator was replaced by a rubidium vapour cell, bringing the accuracy to 2 parts in 10^11, equivalent to one second in a period of more than 1,500 years.

From 1967, the frequency of the Droitwich 200 kHz transmitter was therefore guaranteed to be no lower than 199.999999996 kHz and no higher than 200.000000004 kHz.

In 1978, when two additional transmitters, at Burghead and Westerglen, were brought into service on 200 kHz, a mechanism was put in place to lock their frequencies to the signal from Droitwich.

The move from 200 to 198 kHz in 1988 meant that the carrier frequency was guaranteed to be between 197.99999999594 kHz and 198.00000000396 kHz.

A far cry from the BBC's early years, when it used mechanical tuning forks to get its transmitter frequencies to be accurate to the equivalent of 1 second per day, meaning in practice within about 10 Hz (0.01 kHz) or so of their nominal frequency.

Even so, this was very much better than the standards in the US, where the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) only tightened its regulations in 1932 to require stations to be within 50 Hz (that is, 0.05 kHz) of their assigned frequency.

A UK standard-frequency service had been run since the 1920s by the GPO station at Rugby (callsign GBR) on 16 kHz (a wavelength of 18,750 metres). In 1950, an additional service was opened on 60 kHz (5,000 metres) and shortwave with the callsign MSF, also from Rugby.

The GBR service on 16 kHz closed in 1986. In 2007, the MSF service on 60 kHz moved from Rugby to a transmitter at Anthorn in Cumbria run under contract to the UK's National Physical Laboratory.

Currently, the MSF transmitter guarantees to provide a frequency accuracy of 2 parts in 10^12, equivalent to one second in more than 15,000 years.

One of my first jobs when I joined BBC Monitoring in 1981 was taking accurate measurements of the frequencies of long and mediumwave stations, using a signal generator whose accuracy was checked each morning against the signal from Droitwich.

This work had several practical purposes. For example, the BBC standard at the time for its multi-transmitter networks (e.g. Radio 1 on 1053 and 1089 kHz) was that no transmitter in the network should be more than 0.00005 kHz (i.e. 0.05 Hz) above or below its nominal frequency.

This meant that, in the worst possible scenario, with one transmitter in the network 0.00005 kHz too high and another 0.00005 kHz too low, listeners might hear an annoying fade or "beat" every 10 seconds, generated by the mixing of the two signals.

In practice, the BBC networks were maintained well within

that standard.

Compare that to the very poor frequency standards observed today on 1053 and 1089 by the commercial station TalkSPORT, with rapid beat interference clearly heard, particularly after dark.

TalkSPORT's 1053 transmitter at Droitwich has been measured as being more than 2 Hz off frequency (i.e. more than 40 times worse than the old minimum BBC standard!).

In addition, TalkSPORT fails to ensure audio synchronisation of the signals on its mediumwave transmitters, resulting in echoes being heard as the listener receives the same programme from different sites on the same frequency.

When the BBC longwave service ends, a standard-frequency service on LW will still be available to users in Europe from France's transmitter on 162 kHz. This stopped carrying broadcast programming in 2016 but continues with a time-signal service.

And those with suitable receivers will still be able to use standard-frequency signals from MSF on 60 kHz and Germany's DCF77 on 77.5 kHz (from a transmitter near Frankfurt).

Radio 4's mediumwave fillers, 1978-2024

Now a look at the network of low-power mediumwave transmitters that supplemented reception for Radio 4 listeners who might have had poor reception of longwave.

The fillers were in four categories:

1. To fill part of the "mush" area between the two Scottish LW transmitters at Burghead and Westerglen there was a transmitter at Redmoss (a suburb of Aberdeen) on 1449 kHz.

2. To fill the mush area in Northern Ireland, the Isle of Man and the far north of England between Westerglen and Droitwich, there were transmitters at Lisnagarvey (near Belfast) and Londonderry on 720 kHz, Enniskillen on 774, Brisco (near Carlisle) on 1485 and Wrekenton (near Newcastle) on 603.

3. Various transmitters in Devon and Cornwall. Originally, these were also required because there continued to be regional opt-out Radio 4 programming for South-West England after the 1978 frequency changes, until Radio Devon and Radio Cornwall opened in January 1983.

In Devon, from 1978, the relays carrying Radio 4 UK, along with the South-West opt-outs, were at Barnstable (on 801 kHz), Exeter (990), Plymouth (855) and Torbay (1458).

In January 1983, all four of the above frequencies

switched to carry the new BBC Radio Devon.

The frequency of the Radio 4 relay at Plymouth switched from 855 to 774 to give a MW service to areas of Devon where LW signals from Droitwich were in the shadow of Dartmoor.

3. In Cornwall, the Radio 4 relay at Redruth (on 756 kHz) remained unchanged when BBC Radio Cornwall opened in 1983 as the latter was given its own MW frequencies. Redruth provided coverage to areas where LW signals from Droitwich might have been in the shadow of Exmoor.

4. Radio 4's MW relay in London (720 kHz) was not included in the original plan implemented in 1978. But some listeners in London complained of poor LW reception and so a transmitter on 720 opened at Lots Road in November 1979. Transmissions moved to Crystal Palace in 2001.

For many years, Radio 4 did not announce its mediumwave outlets on the air. But thanks to Andy Walmsley here's a recording of it doing so in January 1982. Note that at that time Radio 4 was still not available on FM in Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland.

All of Radio 4's mediumwave fillers closed in April 2024.

Who else has used longwave?

A look at the use of longwave by other countries over the past 100 years:

By the time the BBC began broadcasting on longwave in July 1924 there were already LW stations in nine other countries:

Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, France (two stations), Germany (two stations), the Netherlands (four stations), Sweden, Switzerland and the USSR.

Stations came and went during the 1920s and 1930s, and by

the outbreak of the Second World War the following 15 countries were on

longwave:

Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Romania, Sweden, Turkey, the UK and the USSR

In addition, Finland, Hungary, Norway, Poland, Slovakia, Sweden and the USSR had transmitters between 300 and 500 kHz (in the gap between what is now the LW and MW bands).

After the disruption of the war, 13 countries had

longwave transmitters at the end of the 1940s:

Czechoslovakia, Denmark, France, Germany (Soviet Zone), Iceland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Romania, Sweden, Turkey, the UK and the USSR

With Sweden and the USSR also still having transmitters between 300 and 500 kHz.

The Copenhagen Plan (agreed in 1948, implemented on 15 March 1950) allocated longwave frequencies to 12 countries:

Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Finland, France, Iceland, Norway, Poland, Romania, Sweden, Turkey, the UK and the USSR

The Copenhagen Plan did not allocate a longwave frequency to Luxembourg, but it continued to use one anyway. It also did not allocate any LW channels to either East or West Germany (neither of which existed as states when the plan was agreed in 1948), but both of them set up stations in the band.

The list of countries using longwave remained stable in the 1950s and 1960s. The 1970s saw an expansion of LW use, particularly by the USSR, which put multiple transmitters on all 15 longwave channels.

Twenty-one countries were allocated LW channels in the 1975 Geneva Plan and used them:

Algeria, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Finland, France, East Germany, West Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Mongolia, Morocco, Norway, Poland, Romania, Sweden, Turkey, the UK and the USSR

But seven countries who were allocated longwave channels in the Geneva Plan never used them:

Egypt, Israel, Libya, the Netherlands, Spain, Syria and Tunisia

Algeria, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland (closed in 1993), France, Georgia, Germany, Iceland, Italy, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Luxembourg, Mongolia, Morocco, Norway (closed in 1995 but returned between 2000 and 2019), Poland, Romania, Russia, Sweden (closed in 1991), Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, the UK, Ukraine and Uzbekistan

The closures of longwave stations picked up in the 21st century. Here are just some of the countries that have left longwave since the year 2000:

2004: Italy closed

2010: Ukraine closed

2014: Russia, Bulgaria and Germany closed

2016: Belarus and France Inter closed

2019: Norway and Europe 1 (a French station with its

transmitter in Germany) closed

2020: Radio Monte Carlo (a French station) closed

2021: Czech Republic closed

2023: RTL (a French station with its transmitter in Luxembourg), Ireland and Denmark closed

2024: Iceland closed

At the time of writing (June 2025) there are just six countries still broadcasting on longwave:

Algeria, Mongolia, Morocco, Poland, Romania and the UK

The BBC's longwave transmitters since 1997

In 1997, all of the BBC's radio and TV transmitters in the UK (on all wavebands) were privatised. All the BBC's domestic stations were bought by a US company, Castle Tower. The UK transmitting stations for the World Service were sold to Merlin Communications.

The new owners continued to transmit BBC programmes under a service contract.

The BBC said it did this to raise funds for the start of digital broadcasting.

Shortly after the sale, Castle Tower merged with another US firm, Crown Communications, with the new company known as Crown Castle International.

In 2004, Crown Castle UK was sold to National Grid plc, the name changing the following year to National Grid Wireless.

In 2007, National Grid Wireless was bought by Arqiva, a subsidiary of the Australian conglomerate Macquarie.

In summary, the BBC's longwave transmitters have been owned by:

1924-1925: Marconi

1925-1926: British Broadcasting Company

1927-1997: British Broadcasting Corporation

1997-2004: Castle Tower / Crown Castle

2004-2007: National Grid / National Grid Wireless

Since 2007: Arqiva

Despite the changes of ownership, the longwave signals on 198 kHz (1515 metres) continued to come from three sites:

1. Droitwich (south of Birmingham): Two Marconi B6042 transmitters, each of 250 kW, installed in 1987. Their outputs can be combined to give a total power of 500 kW.

2. Burghead (east of Inverness): Two Marconi 6046 transmitters, each of 28 kW (modified versions of the Marconi 6034), installed in 1988. Their outputs can be combined to give a total power of 50 kW.

3. Westerglen (just outside Falkirk): The same arrangements as at Burghead.

There is also a fourth, rather special, transmitter carrying the BBC on LW. This is at the Dartford Crossing (east of London), where several micro-power rigs have carried popular AM/FM stations in both northbound tunnels since the late 1980s. They can also be used to carry emergency information for drivers in the tunnels.

UK longwave stations that never happened

In 1997, it was reported that the UK radio regulator (then known as the Radio Authority) might advertise a commercial licence for longwave broadcasting in the UK (on 225 kHz). The idea came to nothing.

At the very end of the 1990s, there was a plan to broadcast a commercial station, MusicMann, from a longwave transmitter on 279 kHz in the Isle of Man. This also came to nothing.

To be concluded...

Sources

BBC Engineering 1922-1972 (Edward Pawley)

World Radio TV Handbook (annual editions since 1968)

Radio Times archive at the BBC Programme Index (formerly The Genome Project)

Development of the BBC AM Transmitter Network by Clive McCarthy

Droitwich Calling (1994, revised 1998 and 2006) by John F. Phillips

The Transmission Gallery: Droitwich

5XX Transmitter Valves Return to Daventry by Rod Viveash

Old frequency lists at the European LW/MW History site

Full text of the 1948 Copenhagen Frequency Plan

Full text of the 1975 Geneva Frequency Plan

Synchronisation of the Radio 4 (UK) transmitter chain on 200 kHz (BBC Research Department)

Longwave transmitter listings by Asiawaves

Andy Walmsley's blog Random radio jottings and his Twitter/X account @Radiojottings

Thanks also to Twitter/X posts by @PaulRowleyRadio, @MikeBrclough and @cl_hart

For other sources, follow the links in the text.

© Chris Greenway 2025